Touring Notes: Iceland

I. Practical Information

index : I. Practical Information : II. Touring Zones

General Remarks

Iceland is a popular cycle touring destination with continental cyclists, though apparently not so popular with British cyclists. The main attractions are the great variety of its wilderness scenery, many quiet roads and opportunities for adventure cycling. It is the most active volcanic location on the planet. It has the largest glaciers outside of Greenland and the poles. It has beautiful fjords, craggy mountains, and lakes with icebergs. There are lush green farmlands, flower-studded heaths, rocky hill-sides, tundra and bare desert. And there is abundant wildlife (best in June/July). Hard-boiled adventure cyclists will find much to amuse them, but the recent and rapid improvement in road conditions means that there are many highly rewarding options available to cyclists not seeking extreme adventures. The drawbacks are the weather and the costs. If you don’t have the physical and psychological equipment to put up with cold, wind and rain, then you may well have a miserable time.

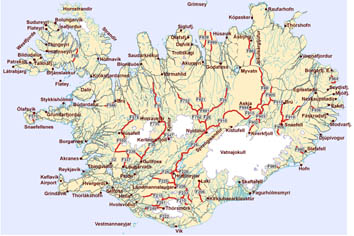

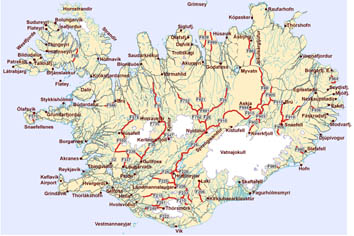

You can, at a rush, do a full circuit of Iceland in about 3 weeks, if you stick more or less to the 1,300km Ring Road that encircles the country. But such a tour would miss much of what is best about the country. At 103,000 sq km, Iceland is almost half the size of Great Britain. Many of the most interesting places are on time-consuming detours off the Ring Road. Whilst the eastern half of the Ring Road is fairly quiet and goes straight through special landscapes, on the whole the western half is busy and its scenery rather less interesting; though of course there is plenty of wonderful scenery in western Iceland away from the Ring Road. So if you only have 3 or 4 weeks, you may get more out of your tour if you concentrate on about half of the island, have some time to get off the beaten track, and leave the rest for another visit.

The people you meet will mostly be other tourists. Tourism has grown rapidly, and in many places you go the tourists greatly outnumber the locals in season. The Icelandic economy benefits considerably from this, but nonetheless one can detect some elements of resentment. Occasionally one is made to feel more like an exploitable resource than a human being. The tourist season is strongly concentrated from the beginning of July to the middle of August. Things start to wind down in late August. Many tourist services operate only in July and August, and most of the rest only from mid-June to mid-September.

These notes were put together after four cycling tours in Iceland over 1994-2005, twelve weeks in all.

Roads

Iceland has long had a notorious reputation for its roads, but it is becoming less and less deserved. You are likely to spend much time cycling on tarmac unless you are deliberately avoiding it. Main gravel roads are mostly adequately maintained, though you are also likely encounter a few poor stretches. If you want to ride bad roads, increasingly you have to make a conscious choice to look for them. But if you want to have adventures on really bad roads, there is a wide choice available, although even the mountain roads are being continuously upgraded.

Iceland is encircled by its Ring Road (Route 1), which is about 1,300km around. Your guidebook might tell you that 200-300km is unpaved, but this has almost all gone (2005), and will entirely vanish before long. The remaining short unpaved sections are almost entirely between Egilsstaðir and Höfn in the east. In the NE, the Ring Road now by-passes Möðrudalur, taking a route further to the NE which is less prone to be blocked by snow. Many significant settlements, especially in the north, are set off the Ring Road; the northern half of the Ring Road between Borgarnes and Egilsstaðir passes through only one town (Akureyri) and three villages. But connecting roads to the outlying villages are often paved.

There are a few tunnels in Iceland. You cannot cycle the Hvalfjörður tunnel between Reykjavík and Borgarnes, but you can cycle all of the rest. Some tunnels are single track with passing places, and the long tunnel near Ísafjörður has a T-junction in the middle.

Iceland has a poor and deteriorating road safety record, which is good reason to avoid busy roads. But on the whole other road users are reasonably courteous to cyclists.

Gravel roads and dirt roads

A gravel road is an all-weather unsealed road, which has been deliberately constructed to a given standard. It is raised on a bed above the surrounding land, which allows it to drain. The builder of a gravel road will generally carry in suitable materials (“road metal”) to surface it, so that the road is initially well-consolidated and reasonably smooth. However the surface will tend with use to become pot-holed and corrugated, the clay particles holding the gravel together get washed out, and eventually the whole thing falls apart into a pile of loose stones, especially if heavier vehicles use the road, until maintenance restores the surface to its original state. This is why quiet roads sometimes have better surfaces than main roads.

Main sections of gravel road are usually adequately maintained, even in the Westfjords. I have travelled in many other countries where the condition of gravel roads is much worse. What can be painful is to encounter a section of gravel road that is undergoing maintenance or in the process of being paved, which may, in its temporary state, be so loose as to be unrideable. It is one of the few circumstances where you may encounter thick mud.

In contrast, a dirt or earth road is simply bulldozed into the ground, or beaten out by the passage of traffic. The surface quality varies with the local soil conditions, and it may puddle or (rarely) liquefy in the rain. If the soil is of the kind that tends to pack down into a smooth hard surface, then a dirt road can be better than a worn gravel road. But in other places the soil may tend to looseness or lumpiness. Major dirt roads do obtain some maintenance, and this may involve laying some road metal onto the road bed to improve its state of consolidation. But at times you may be attempting to ride on unconsolidated loose material, corrugations, or a pile of rocks, and in the worst case this may not actually be possible, even on level ground. If a road is described as really challenging, it may be because you will have to drag your bike through soft sand or loose pebbles for hours and hours.

Information, even recent information, on poorer roads is very subjective. A road that is really bad one day can seem perfectly reasonable on another occasion. It depends not just on recent maintenance or wear, but on the weather, the direction you travel, and how much luggage you are carrying. A loose, lumpy road is much harder with a strong adverse wind pushing your wheels where you don’t want them to go. Some roads are improved by recent rain to damp them down and improve their consolidation, but a few may become sticky. Some lightly-used roads benefit from recent traffic to tamp them down, particularly early in the season.

Road information boards

There are some excellent roadside information boards around the country, some of which show good diagrammatic maps of the roads in wilderness areas. These categorise the roads as follows:

The maps also show the locations of major fords with a V symbol. Whilst this information is of excellent value, not least because it is usually more up to date than any paper map, it can mislead the cyclist. Road surfaces which cyclists find straightforward can be much more troubling to motorised vehicles, and vice versa. A road might be categorised for high-clearance vehicles solely because it has one short bad section or deep ford which the cyclist will soon pass. However stretches of soft surface or loose gravel, appalling to the cyclist, can be found on roads passable by ordinary 4wds, or even ordinary cars. For this reason, it is usually advisable to make separate enquiries of the formation of lesser-known wilderness roads before setting off, preferably from people who understand the needs of cyclists rather than the needs of motorists.

Choosing a bike for Icelandic road conditions

A mountain-bike is a safe and adequate choice for most cyclists. The safe choice has steel luggage racks, no suspension, strong 26" wheels, and tyres with an indented tread rather than knobbles. Some of us choose to ride something a bit faster, preferably informed by prior experience of what will prove adequate for our chosen routes. For provided your bike is strong enough to survive the kind of roads you choose to ride, other details are largely a matter of personal taste.

You need a mechanically reliable bike, as there is little opportunity to buy spares, and most places you will have to do any fixes yourself. You probably need plenty of luggage capacity, bearing in mind occasional long distances between food supplies (especially if you choose interior routes), camping equipment and warm clothes. If you are going on rougher roads, your bike and luggage equipment need to be rugged enough to stand up to a lot of abuse. Steel racks, such as made by Tubus or St John Street Cycles, are a wise investment, as alloy racks break on bad roads, especially alloy front racks. Using front racks spreads the load and improves the bicycle’s handling on hills (though a few cyclists disagree), so I prefer to find a steel front rack than not use one. Single beam rear pannier supports, commonly found on full suspension bikes (eg clamped around the seatpost), will break off in no time if you cross rough terrain with heavy luggage. Ortlieb panniers are strong and waterproof, though there are probably adequate alternatives. Suspension forks or frames will complicate your luggage carrying arrangements, increase the weight you must carry, increase the shaking experienced by parts below the suspension, and absorb your energy. Good racks suitable for suspension forks are increasingly available, but it is important to use the best; I have occasionally seen serviceable racks on a rear suspension bike, but at a very considerable weight penalty. If you are thinking of using a luggage trailer, you should first be sure of its performance in strong side-winds and on the type of roads you intend to use.

I think knobbly tyres are a mistake for Iceland. Knobblies are good for riding in soft mud. Icelandic unpaved roads are generally hard, loose or sandy, and only rarely muddy, even in heavy rain. On balance, knobbly tyres are counter-productive most of the time in Icelandic conditions. A better solution, if you are going to ride on the bad roads, is to bring tyres with an incised tread. If you choose to travel predominantly on tarmac and good gravel, you do not really need the fattest tyres in the shop.

Fords

Although most of the more challenging fords have now been bridged, there remain many fords on remoter roads. Just because a river has a road going in one side and out the other doesn’t mean that it is necessarily crossable at the moment you encounter it, so do think carefully before entering a deep or fast-flowing ford. You should generally carry or wheel the bike rather than ride across all but the smallest fords. This is because the bed of the ford is often very loose, so if you ride it is easy to get stuck and fall off. The water is usually freezing cold and frequently fast-flowing. It is usually best to cross at the downstream edge of the ford where the stream is wide, which is often the shallowest route. Dont cross in bare feet, because there is a risk of damaging your feet on the rocks. Most cyclists carry some sandals or light shoes to cross fords. If you use sandals, they should be fully strapped (not thongs) so that they remain firmly on your feet, otherwise the current will take them away. If you can’t cope with the near-freezing water, bring some neoprene socks, as used for water-sports. If the water is higher than your bottom bracket, you should if possible carry your bike across, so as to keep water from getting in your bearings. This generally means carrying your luggage across separately, a boring task but wise. If the water is turbid (ie, muddy so you can’t see the bottom), it is advisable to first to wade the ford carefully without carrying anything to find the easiest route across. You will normally choose to carry the bicycle across fast-flowing water, as wheeling will be difficult. But in extremis you might choose deliberately to wheel the bike in fast-flowing water to break the force of the current, standing on the downstream side of the bike. If the water is fast flowing and more than half way up your thighs (even that may be too much), or in spate (indicated by smooth-flowing water), you probably cant ford it in that condition. You can retreat, wait for vehicular assistance, or maybe wait for the water level to fall: melt-water streams are higher in the afternoon and in warm weather.

Ford depths vary substantially with season, rainfall and snowmelt. Glacier-fed fords deepen in or after warm weather, and others in or after wet weather. Notable roads with a high likelihood of deep fords are F26 Sprengisandur, F249 to Þórsmörk, F210 Fjallabak Syðri, F261 Fljótsdalur to Hvanngil, F88 Mývatn to Askja, F910 Askja to Brú i Jökuldal (Gæsavatnaleið central section) and F910 Askja to Nýidalur (Gæsavatnaleið west section). I was turned back by the main ford on the Þórsmörk road on a hot sunny afternoon, though I am informed that if I had walked a few hundred metres downstream, it widens and becomes shallower. There are plenty of fords on Landmannaleið and Fjallabak Norðri, particularly the latter from Landmannalaugar to Eldgjá, but these are not normally particularly deep. On Kjölur, there remain only a couple of shallow fords, which were dry when I crossed.

Busy roads

Cycling in the immediate vicinity of Reykjavík is not too pleasant, because the roads are busy, and it is hard or impossible to avoid sections of uncyclogenic dual carriageway. At least the dual carriageways often have a shoulder, whereas some of the busy single carriageway roads are very narrow, which is scary. The worst:

(1) The western Ring Road from Reykjavík to Borgarnes and (to a lesser degree) on to Akureyri. You cannot cycle through the Hvalfjörður tunnel, so you will need to take the bus to Borgarnes in any case, unless you have time for an extended detour around Hvalfjörður. There is no longer a ferry from Reykjavík to Akranes. The western Ring Road is fairly busy the whole way from Reykjavík to Akureyri, and does not represent Icelandic cycling at its most pleasurable. Moreover the scenery is not very interesting for an extended section from around Borgarnes to Blönduós.

(2) The south-western Ring Road from Reykjavík to Hvolsvöllur, especially the first section to Selfoss. This road is particularly narrow and busy and has no shoulder. This is a shame as the scenery from Reykjavík to Hveragerði is quite interesting. From Hveragerði to Hvolsvöllur is through flat farmland. Beyond Hvolsvöllur, the road gets much quieter and more interesting.

(3) Keflavík Airport to Reykjavík, especially the last 12km into Reykjavík. There is now a shoulder you can ride on for much of the way. Increasingly this road is being widened to a dual carriageway.

I prefer to take the bus to avoid the above roads, though plainly this can be costly.

Opening of Mountain Roads

An important factor in deciding when to go is whether you want to travel any specific interior routes or remote high passes. Unpaved roads which close for the winter (or longer) are usually designated as “mountain roads”, and are usually identified by the letter F prefixed to the road number. Some of these routes are impassable until quite late in the summer, and sometimes one or two might fail to open at all. The mountain roads of most importance to tourism are opened with bulldozers if necessary at the beginning of July. Cyclists can, if they choose, travel these routes before they officially open. Usually most of the snow will be gone a week or two before they open officially, but the roads can be soft and muddy at this stage, because the sub-surface can still be frozen, impeding drainage. However if you attempt them too early you may have some extended snow to cross. I met a cyclist who used an interior route a month before it was open, and he said it took him 5 hours to cross a 5km snow-band. Roads usually remain open until at least late September, and Kjölur can remain open into November.

Of course, nothing can be guaranteed. In 2001, two metres of snow fell in NE Iceland in late May, making the opening of some roads much later than usual. Officially, Gæsavatnaleið did not open that year, though some cyclists still made it across. In 2005 there was a snowfall in the NE in late August, and roads around Askja closed early. You can check the status of roads on the road administration website. Notices are distributed to petrol stations and tourist offices, and updated weekly.

more detail (116kB)

Route | Typical opening date |

Kjölur (F35); Jökulsárgljufur (F862); Kaldidalur (F550) | Late May to mid June |

Askja (from north or east) (F88, F894, F910 Askja to Brú) | Early June to early July |

Fjallabak Norðri north (F208 Landmannlaugar to Hrauneyjar) | May |

Landmannaleið (F225) | Early June to early July |

Fjallabak Norðri east (F208 east of Land’gar); Fjallabak Syðri (F210, F261)) | Mid June to mid July |

Sprengisandur south end and NE approach: Hrauneyjar to Goðafoss (F26) | Late June |

Sprengisandur NW to Varmahlíð (F752); Snæfell (F910 east of Brú, F909) | Late June to mid July |

Sprengisandur N central to Akureyri (F821) | Early to mid July |

Gæsavatnleið (F910 Askja to Nýidalur) | Early to late July |

Climate and Daylight

The climate is cool marine temperate (“sub-arctic”), and weather tends to be very changeable. Whilst a light snowfall is possible in summer, you are unlikely to have a heavy snowfall from June to September. Because of the effect of the sea, the temperature does not vary much over this period, although in my experience the weather deteriorates noticeably towards the end of August, and the arrival of true darkness in mid-August reduces overnight temperatures. The summer (mid-June to mid-September) can be compared to Northern Scotland in April to May. Expect to cycle in temperatures of 10°C to 15°C most days, but be prepared to cycle in temperatures as low as 4°C (especially in the highlands) and sometimes well over 20°C. You can have a light frost at night even in summer, even by the coast. In the highlands, you will often be camping at altitudes of around 600m, and temperatures are significantly colder than by the coast or in the south.

Rain is frequent, but is mostly showery or drizzly. The wettest part of Iceland is the south, especially around Vík í Mýrdal, and the west and north-west are also wetter than average. The north and east is markedly drier, especially the NE interior. The southern and western highlands are very wet, but the highlands to the north of Vatnajökull are much drier. The weather often seems to clear up later in the afternoon, and I have usually managed to cook my dinner in the dry. Reykjavík and Akureyri seem to enjoy pleasanter micro-climates than much of the rest of the country.

For many people, the wind is the worst aspect of Icelandic weather. It blows often enough to keep your daily distances lower than you might otherwise expect, and occasionally blows strongly enough to disrupt your planning. So make sure you have enough food in case you dont get very far tomorrow. To make this clear, on a windy day, such as can easily occur once or twice a week, do not be surprised to have to struggle to achieve 8-10 km/h on a flat, paved road, and on an unpaved road you might be reduced to 5-6 km/h; and in a bad wind such as occurs once or twice a month you won’t be cycling at all. Take a good tent if you are camping, and ensure you can cook in the porch, as your stove won’t like the wind. In most parts of Iceland, the dominant wind is from the southwest, but in the south it usually comes from the southeast. So in theory it is marginally easier to cycle clockwise around the country. But don’t blame me if it doesn’t work like that for you. Annoyingly, the weather is frequently calm overnight, and the wind gets up mid-morning.

Statistically, you are due an average of 5 to 6 hours of sunshine a day in mid-summer, which sounds like quite a lot. But with 20 hours or more of daylight in mid-summer, that means that about three-quarters of the time it won’t be sunny. So after a couple of sunny days you might hardly see the sun again for a week. On my first visit, I experienced numerous consecutive sunny days, but such occurrences are rare. Normally you will have to put up with a lot of dull weather. There seems to be a bit more sunshine in late spring and early summer, though of course this cannot be guaranteed. The north and east are markedly sunnier, especially the NE interior.

There is perpetual daylight through June to late July, and it barely gets dark for about 90 days from early May to early August. It remains light beyond 21.00 throughout August. Because sun overhead is about 13.45, you get light beyond 19.30 even in late September. Iceland is on GMT without any summertime adjustment.

Maps and Guides

I have met several cyclists who have survived without maps. You can work out most things from guidebooks, free hand-outs and the excellent roadside information boards. If you want to have more control over your fate, you will want maps. I prefer to use the LÍ 1:250,000 maps. These cover the country in nine sheets, but by buying the double-sided versions you can reduce this to five. They now also sell an alternative 1:250,000 edition with more colour and tourist information but less detailed contours, which covers the country with just three large single-sided large sheets; they are visually similar to the Mál og Menning sheets, and tend to be more up-to-date than the 9-sheet version, and have a clearer method of indicating road quality. The advantage of the older LÍ maps is greater detail of the topography (20m contours, clearer print). One problem with the LÍ maps is that prominently marked names are often not those seen on signposts, and some impassable abandoned tracks are shown. More colourful and tourist-friendly are Mál og Mennings four 1:300,000 sheets. However they only have 100m contours, don’t always show fords, and are more selective in showing minor roads. They have recently put out a map of the main highlands, which appears more comprehensive and includes GPS datum points for road junctions, potentially useful if you intend using very minor routes. Maps can be bought at many tourist locations and supermarkets in Iceland, or, at the same price, by mail order from Dick Phillips (01434 381440). A 1:100,000 series is also available, however it is of more use to walkers as the maps tend not to be updated.

If using a compass, be aware that magnetic deviation is high (around 20 to 25 degrees West). There are a number of areas where the compass misbehaves due to magnetised minerals in the ground.

The original Lonely Planet to Iceland, Faeroes and Greenland was sympathetically written by Deanna Swaney, surely the best of Lonely Planet’s authors. The recent update by a different author has some ill-judged comments about cycling. You can also get an adequate Rough Guide.

Accommodation

A free booklet detailing most guesthouses and organised campsites is widely available. Hotels and guesthouses with made-up beds are very expensive, and mostly booked up in the high season. There is plenty of “sleeping-bag accommodation” (ie, bring your own sleeping-bag), in guesthouses, hostels and schools, often self-catering. It tends to fill up in popular locations, so you should always phone at least a day ahead in the high season if you are relying on it. In Reykjavík, you may need to book a couple of months in advance to obtain even sleeping bag accommodation in the high season. Because of long distances and the difficulty of predicting how far you will cycle tomorrow, most cyclists will expect to camp, though it can generally be avoided outside the most remote areas if you plan carefully.

Please do not treat the emergency huts as bothies. As a result of misuse, they are becoming damaged and disgusting, and the equipment and supplies are no longer available for genuine emergencies. It is illegal to stay in them except in a genuine emergency. If you do go inside to shelter from the weather for a little while, please don’t leave your litter behind, because no one collects it.

Camping

There are plenty of campsites in Iceland, and almost every town or village has one. In 2005, the typical price was 600-700 K per person per night. Some are free, or don’t always collect the fees. Many campsites do not have hot showers, and if it does you often have to pay extra to use it. Many villages have nice warm subsidised swimming pools you can visit instead, if you arrive before they close. The price of a campsite is often unrelated to the quality of its services. You can pay less for a site with a free hot shower and indoor kitchen than for one with a cold tap and a chemical loo.

There is an enormous campsite with free hot showers in Reykjavík on Sundlaugvegur (the continuation of Borgartún) about 4km east of the city centre, between the Laugardal swimming pool and the youth hostel. Be careful of your belongings at this campsite, and lock up your bicycle. You can often pick up camp stove fuel left behind by other campers here.

I believe it is usually desirable to make use of organised campsites when they are available. Organised sites make proper provision for the disposal of human waste and litter, which can otherwise damage the very thing the tourist has come to see. Indiscreet or irresponsible wild-camping may prejudice the local population against low-spend tourists such as cyclists, and you may no longer be seen as “low impact” tourists. I appreciate that some Icelandic campsites are overpriced and uncongenial, and the cyclist has less opportunity than the motorist to choose between them.

In theory you can wild camp anywhere, provided it is not someone’s field, nor within 1 km of an organised campsite, nor in a national park or national nature reserve (look for the green leaf sign). However finding somewhere to wild camp is not always easy, particularly in well-farmed districts where the land tends to be fenced. It can be difficult to find suitable ground, or else to find shelter from the wind or proximity to a water supply. You can try knocking on farmers’ doors to ask for permission to camp on their land, though success is far from assured, since some Icelanders resent the tourist invasion. You are most likely to be successful if you are female and youthful, etc.

Camping terrain varies from very hard, where you will have to hammer strong pegs in, to very loose, where you will prefer broad pegs and be putting rocks on them. I know it seems fussy, but I actually take two sets of tent pegs for the varying conditions.

Only small areas of Iceland have the strict reserve status that requires you to camp in organised campsites, but confusion is caused by a multiplicity of lower status “reserves” covering very large areas of the country. Also you often see signs intended to discourage wild camping – for example information boards remind you to use campsites in national nature reserves, even though you are not, at that location of that notice, in the reserve; signs apparently marking the boundary of a nature reserve can be posted several km before the actual reserve boundary. Some campsite owners put up “no camping” notices of no legal force in order to usher you in the direction of their facilities. Other misleading signs saying “no camping” may really mean “no overnight parking” or “motor vehicles must not leave the road”, and walkers and cyclists may be within their rights to camp at such a location. The main areas where you cannot wild camp are Þingvellir, Þórsmörk, Landmannalaugar, Eldgjá, Skaftafell, Mývatn, Jökulsárgljúfur, Askja, Herðubreiðarlindir, Hveravellir, Nýidalur, and Flókalundur. In several of these areas, reserve wardens do regular circuits to enforce the rules.

Camp Cooking

Gas cylinders are often available at petrol stations, etc. It used to be the case that white gas was available from a camping store in Reykjavík (but nowhere else I am aware of), but this camping store has either closed or moved (2005). Buying petrol for your petrol stove can be trickier than you might imagine, because many petrol stations are now card automats only, and if it takes your credit card (they usually didn’t like mine) there may be a stiff minimum charge. So I sometimes had to wait for a motorist with the right card, and negotiate with them rather than the staff. Alcohol for Trangias can be obtained in a limited number of locations (usually garages), but is rather expensive. It is worthwhile checking out major campsites, especially Reykjavík, for fuel left behind by other campers.

Supplies

On the whole there are more shops than you might expect given the sparseness of the population. Practically every village of more than about 150 people has a shop and a petrol station. Sometimes the shop is the same as the petrol station. However with improved roads and increasing numbers of unattended automat petrol stations, some small village shops are closing (eg Stöðvarfjörður). There are also some remote petrol stations with a shop, eg, Brú (between Borgarnes and Blönduós), Fagurhólmsmýri (20km from Skaftafell – actually this one looked a bit dead when we went past on the bus in 2005, possibly because there is now another petrol station about 5km closer to Skaftafell) and Ásbyrgi. However there is little food to be had at the petrol station at Þingvellir. Beware of place-names on the map that amount to no more than a couple of farms. It is still common for food-shops to shut at 6pm on weekdays, early on Saturday and be closed all day on Sunday. In larger settlements (eg, over 1000 people), you will usually get shopping until at least 8pm on weekdays, though there may still be early closing on Saturday, and Sunday hours may be brief. Petrol station shops often have longer hours, though there won’t be much food available at the petrol station if the main food shop is elsewhere (eg, Kirkjubæarklaustur, Blönduós). Shopkeepers Holiday Monday is the first weekend in August.

Nevertheless, there are some long distances where you can’t get any food. For example, there are no shops from Mývatn to Egilsstaðir, or from Ísafjörður to Hólmavík. Generally there is nothing available on interior routes, though there are some limited and expensive supplies at Landmannalaugar and Húsafell.

Because of the fridge-like temperatures, fresh food can usually be kept for a few days in your pannier. There is a high potential for a food purchase “accident” in Iceland. Much prepackaged fish and meat is salted (“saltað”), and will need soaking in water for a day or two to make it edible. Any cooked meat with the syllables “hangi-” in its name will be unbelievably heavily smoked. Many products sold in the same packaging as milk, and having the word for milk “mjólk”, are actually some kind of yogurt: if you are looking for normal milk it is “nýmjólk” (whole milk), “lettmjólk” (semi-skimmed), “undan renna” (skimmed milk) or G-mjólk (UHT).

Drinking untreated water from streams is generally OK if the water has come down from the hills rather than run across farmland. You should avoid taking water from larger rivers, especially glacial rivers and glacial outwashes, which have a very high load of sediment, which will often not settle even if you leave it to stand. Even lakes fed by glacial rivers can be opaque with rock-flour, though you can drink this stuff if you have nothing else. There can be long distances between acceptable water supplies in some remote desert places. Many of the small streams in the interior, invitingly marked on your map, will be dry when you pass as they carry spring melt-water only. Lava fields and sand-flats are porous and often have no surface water.

Bike Shops and Repair

It is wise to ride your bike carefully on bad roads, because a hard-to-repair breakage could seriously inconvenience you. The commonest mechanical problems cyclists suffer (beyond the routinely reparable) are a broken rack, especially a front rack, and broken spokes. Some people also manage to wreck their wheels or gearing. If you are going to ride on bad roads, you are much safer choosing steel racks. But if you are sticking to better roads, these days you can probably get away with good quality alloy racks. On a long tour, you should be prepared to regrease your bearings, as the road conditions are not kind to bearings. Fit a new high quality bottom bracket before setting out if you have any concern that it may need maintenance or replacement in the near future. Your luggage carrying arrangements should have space to carry more than the usual quantity of luggage, with warm clothes, camping kit, and space for several days food, depending upon the routes you choose. On interior routes, it is occasionally necessary to carry water for an overnight camp, which can add considerably more weight. Make sure your racks and panniers can stand up to carrying the luggage you will need on the roads you will travel.

There is one good bike shop in Reykjavík, and a couple of less good ones. If you are somewhere remote, and need something difficult urgently (eg a wheel), the best tactic may be to give them a call and get them to send it on the bus, though that may take a couple of days if you are in the east. The next best shop is in Akureyri. After that, there are smaller shops in Selfoss, Ísafjörður and Egilsstaðir, and a part-time bike repair man in Höfn (ask around to find him).

Otherwise you will have to go to a car or agricultural repair shop and ask for some help. They won’t have any spare parts, but do have some tools and are surprisingly inventive and helpful. They will often do a weld for you, even an aluminium weld in some places. The first time I visited Iceland, on an unsuitable lightweight bike, I cracked the frame and broke the rear axle. The former was welded by an agricultural engineer, but the latter I had to put with until I got home.

Things to Take

Take your own bike. You can hire a reasonable bike in Reykjavík (see info at http://www.icebike.net/), but from what I’ve seen they won’t stand up to a lengthy tour with heavy luggage. Take any routine spare parts you might need on the road. It is essential to carry spare brake blocks, as they wear down quickly in wet weather on gravel roads, and you will quickly wreck your wheels riding with worn blocks. Take a small bottle of chain oil (or cadge engine oil off motorists). It is a good idea to take spare spokes sized to your wheel, and the tools you need to extract your block, though you can borrow a large spanner. One or two flexible “emergency spokes” which can be fitted on the block-side without special tools are also a good idea, but remember to prepare them before packing them.

If you intend camping, you need to be confident of your tent and your ability to put it up in a strong wind; take a couple of spare pegs and a pole repair. With the windchill and showers, it feels cold much of the time, so take suitable clothes (or buy some on arrival – Icelandic woolly jumpers, hats, etc, are a popular souvenir). In wet weather I like to use neoprene gloves (as used for watersports), as well as taking some windproof fleece gloves for when it’s not raining. It is very difficult to find milk powder in Iceland, so take some from home if you like to have milk when in remote places.

Health

Use sun-cream and lip protection. With that ozone hole and wind you need it even on overcast days. Some people have difficulty getting a proper night’s sleep because of the lack of darkness, but I think most get used to it. When wild-camping, carry out your toilet functions responsibly, and well away from water-sources. Pour soapy water onto the ground, not back into the stream or lake.

Security

Iceland is probably one of the most secure places in the world, and in small villages you will not even think to lock up your bike. Some petty theft and damage does occur, particularly in Reykjavík and Akureyri, where there is a drug problem. There is a local habit of getting drunk and disorderly on Friday and Saturday evenings and at public holidays, which is mainly an issue in larger towns. But it also extends to popular wilderness campsites on certain summer weekends and public holidays, eg, Húsafell, Þórsmörk and Ásbyrgi.

Annoying Animals

There are annoying flies in places with bushes or marshes, however they mostly don’t bite, and hide away if the wind is strong. The worst place is around Mývatn, where you might be grateful for a head-net. Some cyclists have reported mice biting holes in their panniers or tents to get at food. Since food is more expendable than your equipment, it makes sense to keep food in plastic bags in your tent porch. Most Icelandic dogs are well behaved, but a few are a serious nuisance. I have had a couple of incidents with mad Icelandic dogs, which I didn’t know how to deal with because they run very fast and throwing stones is not in the culture.

Arctic terns (elegant birds related to gulls, with narrow wings and a black cap, making loud clicking and screaming sounds) are common and are aggressive around their breeding sites. Mostly they try to surprise you by suddenly making loud noises close behind your head, but sometimes they hit your head with their feet, or crap on you. So wear a hat. They go for men more than women. If you hold something up higher than your head (eg, your pump), they will attack that instead. Arctic skuas and great skuas (silent mottled brown gull-sized birds with a pale wing patch, the smaller arctic skua having tail streamers) are relatively uncommon, but can be more frightening. They are most frequently encountered on the flat stony wastes in the south, and near large sea-bird colonies. They may swoop down straight at you, forcing you to duck. Fulmars (the commonest cliff-nesting gull-like bird, having no distinctive markings) are not normally aggressive, but if you harass them they will spit foul-smelling sticky vomit at you.

Money and Prices

The Icelandic Króna (plural Krónur) was 110 to the UK pound in 2005, 133 in 2002 and 150 in 2001, so it has been getting substantially more expensive. Every reasonably sized village has an ATM, and plastic is readily accepted in most places.

Most food is expensive, especially bakery products, meat, cheese, chocolate, crisps, etc. In small village shops, it is considerably more expensive than at main supermarkets. Alcoholic drink is outrageously priced and sold only in special shops with short opening hours. Even fish isn’t cheap. I buy a lot of smoked fish, not because it is cheap, but because other things are more expensive. Milk products are usually more reasonably priced. For some unknown reason, in 2005 certain chains of supermarkets (Bónus and Krónan at least) were selling apples and other common fruit and veg very cheaply. If you are on a tight budget, eat a lot of oats, raisins, pasta, baked beans and smoked herring: oats are generally sold under the Danish Sol Gryn brand in a plain box that would would leave you guessing as to its contents if you didn’t know the name. Restaurants and cafés are expensive and rarely worth writing home about. Accommodation with made-up beds is generally very expensive. Simple sleeping bag accommodation outside Reykjavík is generally around 1500 to 2000 K. In 2005, mountain huts were generally charging 1800 K. A shower at a remote mountain hut is 300 K. Buses are expensive, especially on the more remote routes that cater mainly to tourists. You can see some prices at http://www.bsi.is/.

Transport

You can generally put your bike on a bus, provided there is space. You are likely to be charged 600K to 1000K per journey for the privilege. If a journey involves a connection with a different company, you may have to pay twice. Long distance buses depart from the BSÍ terminal in Reykjavík. There are only one or two buses a day on most routes, though they are several a day to Selfoss and Borgarnes, and up to three a day to Akureyri. There are only three buses a week to Ísafjörður and Hólmavík. If you are between Akureyri and Höfn, you will probably not be able to get to Reykjavík by bus on the same day. From Reykjavík to Egilsstaðir or Ísafjörður, it may be cheaper to fly. In high season, there are regular buses on the main interior routes (Kjölur, Sprengisandur, Landmannaleið, Mývatn-Askja), which are useful for rescue purposes. Bus fares are very high on these interior routes. Timetables and prices are on the web at http://www.bsi.is/.

You can put your bike on the Flybus to or from Keflavík international airport on the same basis, though you may have to wait for one or two to go past before you find one empty enough to take your bike. Flybuses have now wised up about charging for bikes, and you are unlikely to get on free. This service does not run all day, only when there are flights leaving or arriving, although increasingly this is most of the day. Flybuses now use BSÍ like other long distance buses.

Bus companies have a parcels service. You could use this to send some luggage ahead, if for example you don’t need it for a while. It seems possible that you could box up a food package and send it ahead for collection at an interior location, such as Nýidalur, to ease a long interior crossing. We thought about this, but decided we preferred the security of knowing we had our food with us. You could also have spare bike parts sent to you from Reykjavík this way.

Getting There

With increasing competition between Icelandair and Iceland Express, (web sales only: http://www.icelandexpress.is/) ticket prices have come down. Sometimes Icelandair is cheaper than Iceland Express. Dick Phillips (an IT operator specialising in no-frills Icelandic travel arrangements, 01434 381440) offers a special cyclist package attached to an Icelandair IT fare that in the past saved you money compared with an Icelandair flight-only deal, though Icelandair may now be offering its best prices to all-comers. Both airlines charge for bicycles – Iceland Express charged me 1500 K per flight segment in 2005, and I understand the Icelandair price is now 2000 K. Do not confuse Icelandair with Air Iceland, the latter provides local flights only.

In summer you can travel by ferry from the Shetlands to Seyðisfjörður in east Iceland via the Faeroes with the Faeroese company Smyril Line. The Shetlands are accessible by ferry from Aberdeen and the Orkneys. You will sometimes have to stop over in the Shetlands and/or the Faeroes for a couple of days, which you may treat as a welcome opportunity. Smyril Line also serve Bergen in Norway and Hantsholm in Denmark. The timetable and practicalities vary considerably from year to year. Smyril Line seems to be suffering from increased competition from the airlines: it was making unusually cheap offers in 2005, and also cancelled the last sailing.

Arriving at Keflavík International Airport

The international airport is at Keflavík, 50km from the centre of Reykjavík. Do not confuse this with Reykjavík city airport, adjacent to the city centre, which is for small aircraft on domestic flights only.

Many flights arrive late or very late in the evening, though guesthouse owners in Reykjavík do appreciate the possibility of you turning up at 3am. There is an ATM where you can get some Krónur to the left in the concourse after baggage retrieval; the ATM in the lounge area currently only issues foreign currency. If you want to stay near the airport, then there is a campsite in Keflavík town, about 5km from the airport, which you will see signposted from the main road to Reykjavík. There is also a youth hostel at Innri Njarðvík, about 8km from the airport, which you should book in advance, especially if arriving late. It is on Njarðvíkurbraut, which is a left turn off the main road to Reykjavík. Coming from the airport, don’t take the first left turn signposted to Njarðvík (the turning by the petrol station and supermarket), nor the next one signpost Innri Njarðvík, but carry on to the following left turn, which is Njarðvíkurbraut.

It isn’t a very nice ride from Keflavík to Reykjavík. There are tales of cyclists riding this road in bad weather, and changing their ticket to leave the country as soon as possible. I generally prefer to take the Flybus, see above. If you do ride it, although it is a mostly flat 50km, expect slow progress since it is often very windy, especially near Keflavík. You can take a pleasant detour along a quiet paved road along the north coast of the peninsula for about 15km in the vicinity of Vogur. Be aware the road along the south coast of the peninsula from Grindavík to Krýsuvík is a very rough dirt road (“worse than anything I rode in the interior” wrote one cyclist), not advised if you are under any time pressure. But you can avoid Reykjavík entirely by this route, heading for Hveragerði or Þorlákshöfn; food is available at Grindavík.

Once you get to the turn for Hafnafjörður, there is 12km of mostly motorway-like road to the city centre, up and down some modest hills. Even with a detailed map, it seems hard to avoid most of it. Detouring through the centre of Hafnafjörður avoids a short stretch at the price of an extra hill. Make sure you follow signs for Reykjavík-S or Sentrum (which means Centre), not Reykjavík-A (“A” stands for East). After passing the turn-offs to Kópavogur, you should see a cycle/pedestrian bridge crossing over the main road at the bottom of a hill. You can leave the road and cross this bridge, which will lead you onto a quiet suburban road taking you up a hill to the Öskjuhlíð, a curious dome-shaped building at the top of the hill, beyond which you should be able to see where you are going. From Öskjuhlíð you can cycle on a mixture of cycle/pedestrian ways to the BSÍ bus terminal or the town centre. Cyclists are legally permitted to cycle on the pedestrian walkways alongside main roads in Reykjavík, except in the central shopping area.

Other Sources of Information

The main source of all things on cycling in Iceland is Mike Erens’ Iceland Pages. Mike is a Dutch cyclist whose site includes an attractive cycling guide to the country, photos, descriptions of tours, and a comprehensive collection of links to other people’s tours and information. It is a great resource for deciding where you want to go. Mike’s own tour notes are useful. Like me, he made several instructive mistakes on his first tour to Iceland. On one tour, he chaperones a cyclist who is not prepared for the conditions.

I suggest looking at the website of the Icelandic Mountainbike Club, which includes guidance on choosing a bike and luggage suitable for a tour in Iceland. They also have a message board, through which some kind person might give you advice, or set you up with a companion for your tour.

Dick Phillips (see “Getting There”) is the fount of all wisdom on things Icelandic, to my great gratitude. He is also a strong cyclist. He produces a leaflet on cycling in Iceland for his customers.

The Rough-Stuff Fellowship website includes some tour descriptions and photos by the present author, including more detail on the Askja route.

See page II of this article for information on specific touring zones.

index : I. Practical Information : II. Touring Zones