| Guidebooks and maps | Flights | Accommodation | Food | |||

| Security | Health | Weather | Trucks and buses | |||

| Alternative routes | GPS | Roads | Those crowded roads | |||

| Acclimatisation |

This was Colin’s initiation to cycle camping, something which Tracey hadn’t done for 10 years. When laden we carried about 35 kg between us.

Guidebooks and maps

We got most of our information from the Footprint guide. We tore out the pages of interest and took them with us. The South American Explorers have trip reports at their Cusco office. Kevin A. Kirk has written interestingly about road cycling through the Sierra, but there wasn’t much about the routes we had in mind.

Peter Frost’s book Exploring Cusco is invaluable, but so far as we know it can only be bought in Peru. Omar Zarzar of Ecomontana wrote a book Por los caminos de Perú in bicicleta describing miscellaneous rides throughout the country, including Calca–Quillabamba. This can be found (with difficulty) at the Plaza de Armas in Cusco.

Walter Sienko’s rather dated book is still useful though it doesn’t go into great detail. (Latin America by Bike, The Mountaineers, 1993.) Hilary Bradt’s Peru and Bolivia is valuable if you plan to ride trekking routes.

The IGN publish topo maps at 1:100000. These are expensive. They can be bought from Stanford’s, Omnimap, and the SAE. The surveying is very old and roads are often labelled as footpaths and vice versa. The maps are usually accurate to a couple of hundred horizontal metres. We used our scanner to make A4 photocopies of the sections we needed and carried them in a plastic document folder – a great improvement on the unwieldy originals. In spite of their drawbacks they are a superb series of maps.

Lima 2000 publish a map of the Sacred Valley. This can be bought from Stanford’s or at Cusco.

We took a GPS unit, and the maps on this site correct many of the errors in the published maps.

Flights

On our transatlantic flight (Iberia) we were allowed 2 pieces of luggage with no weight limit. Locally we flew with LAN Peru, having bought the tickets in the UK. We were told that the bikes needed to be boxed and would be flown as sports goods at an extra charge payable at the airport, but that they would be additional to our weight limit. There was in fact no extra charge. Someone at the South American Explorers said that tickets bought abroad (at a higher price) carry extra privileges. LAN seem to be efficient and have shiny new planes.

We dutifully reconfirmed our return flights and had no problems.

Accommodation

Cusco and the Sacred Valley have all levels of hotels. Away from the tourist centres there are a few basic hostals but they are sparsely spread and to do our routes you will have to camp. Sometimes it was hard to find suitable campsites because of the mountainous terrain. This was our first attempt at wild camping so we didn’t have much idea about how to do it. We were also unsure of the security situation.

Food

Cusco has a vast range of restaurants, and they have real wood fired ovens for pizza. We particularly recommend Green’s, Macondo and the rather kinky Fallen Angel. Also, in a slightly different price bracket, the Monasterio serves excellent food.

Small restaurants for the local people will be found in almost every significant village. They serve carbo-rich set meals for about s2.50 (50p/60c), soup and main course with rice and potatoes. More upmarket places also have a ‘carta’.

The beef is inexpensive and surprisingly good. Alpaca is often available and gamey.

There are good small supermarkets in Cusco, Urubamba and Pisac, selling things like packet soup and cakes. In the villages the shops sell basics: pasta, rice, milk powder, ‘quaker’ (instant porridge), often bread rolls, sometimes fresh veg, sometimes cheese. Markets are the place to go for fresh veg and cheese. Quality can be very good, with perfect avocados and delicious fat pink bananas.

Beware of the sweetened bread: it can be disgusting. The Pakaritampu at Ollantaytambo makes its own bread which is excellent.

Cusqueña malted beer has an interesting but rather sweet flavour. The Peruvian red wines Tacama and Ocucaje are fruity and drinkable (which is the opposite opinion to that expressed in the Footprint).

Coffee is dreadful. Sienko’s reference to ‘awful boiled sludge’ is still accurate.

Kerosene is widely advertised in the villages.

Security

The Sendero Luminoso is no longer much of a threat but organised crime against tourists remains significant. When we arrived we found that there had been a spate of sexual assaults against taxi passengers by their drivers in Cusco. Strangle robberies still take place.

Soon after we got back we read the following account in the Thorn Tree, written by people who’d been there at much the same time as ourselves:

We were heading north into Cuzco ( Peru ) and 20 km out at 7:30 AM on the main road we were ran off the road by 8 men in 2 cars with pistols. They pinned us down and choked me till I passed out. My $ belt was gone but they didn’t get my wife’s. We carry a holster style $ belt that fits under the armpit which is probably the best kind as in a crowd you can always hold your elbow tight to your body and in turn feel its there. We think it took these guys too long a time to find just one of them and left my wife’s. This was truly a very well excecuted operation with not a word spoken except our yelling and thrashing. |

Apart from systematic crime of this sort there is opportunist theft by the campesinos. This is almost always surreptitious and non-violent, and we’ve no reason to suppose that Peru is worse than anywhere else.

If we’d known before setting out what we know now, we’d have thought twice about going.

Health

Colin had a couple of stomach upsets, both times after eating in good hotels. Tracey got bitten badly by insects in the jungle and 6 weeks later is still scratching. Don’t economise on insect repellent.

Dogs were very little trouble, though rabies is endemic so take care (and get yourself jabbed before going). El Condor Pasa will drive you to the edge of insanity.

Weather

We were there in August. It was hot and sunny in the jungle. In the Sierra it was variable. In good periods it would dawn sunny; cloud would start to appear in late morning or early afternoon, clearing later in the day. In bad periods there were spells of cloud, rain, snow, thunder, and occasional bursts of sunshine, none of it respecting the time of day. In all we probably averaged 3 or 4 hours of sunshine per day in the Sierra. We would certainly have liked more. We don’t know if we were unlucky.

Yearly variation in climate depends on El Niño, and is partially predicatable. Ivan Viehoff reckons that 2003 will be a dry

The wind in the Sierra blows up the valleys and when otherwise undecided from the north west. It blows from Cusco to La Paz.

Acclimatisation

Don’t plan to cycle high passes without reading up first on the medical effects of altitude. We knew from earlier experience that we adapted quite well, otherwise we’d have had to take things more easily. Strength and fitness are no protection against altitude sickness, although they do mitigate the weakening effects of a thin atmosphere.

Roads

The interesting cycling in Peru is on unsurfaced roads or on foot-, cattle- and bridle-paths. The unsurfaced roads were never good (Walter Sienko has a daunting picture) and fell into disrepair during the period of the so-called Shining Path. Recently the government has put a lot of effort into restoring them, and road works are encountered everywhere.

Even at their worst the dirt roads are never as bad as in Chile, and at their best they’re pleasant to ride on. The surfaced roads are impeccable.

Peruvian engineers cut roads through loose rock without shoring them up. Consequently they suffer rockfalls for an eternity.

Those crowded roads

When we returned to the Sacred Valley from Quillabamba we met a French cycle tourist on a road bike with a trailer and a machete. At Pisac we met 3 Australian mountain bikers visiting the ruins. They had come from the Cordillera Blanca, which had been warmer. At the Hotel Pisac we encountered the KE group, who weren’t very keen to talk to us. And around Urcos we passed a Dutch group, again on road bikes. There might have been a dozen of them.

Trucks and buses

We took a truck back from Tinqui to Urcos for 5 soles each. Trucks are the main public transport away from the towns and run more frequently than buses. You sit on the top with all your luggage, including bikes. They are uncomfortable but nowhere near as scary as you might think, in fact almost enjoyable.

We also used buses on our last ride near Cusco, the bikes going on the roof.

Alternative routes

Huchuy Qosqo. We had originally planned to ride from Cusco to Huchuy Qosqo, a route which is mentioned in several places, and of which KE have an excellent photograph. We found that it needed more time than we had available (people say 1-2 days, but they may assume that the route climbs to the altiplano from Sacsahuaymán which makes very little sense: climb from Corao or Chinchero instead). Worse, we were told that the ride was exposed and dangerous – hence the wonderful photograph.

Apurímac valley. We were tempted by the ride from Cusco through Paruro to Pillpinto. The Footprint is quite lyrical about the higher reaches of the Apurímac.

Cusco – Arequipa. This is a natural route through Yauri, Chivay, the Colca Canyon and Huambo taking in many of the best sites in southern Peru. Evidently some people ride it. We considered it seriously ourselves, but rejected it because it didn’t leave enough time for other destinations, and because we were uncertain of the logistics. It could well be combined with the previous route.

Puno – Arequipa. A Dutch cyclist did this route over the Abra Toroya Pass (4700m) in 2000. He said that it was the best part of his cycling trip through Peru. “It is about 330 km and you can do it in 3 (long) days. It is all beautiful altiplano scenery, with lots of llamas, flamingos, lakes and snow-topped volcanoes. Except for the first 100 km the road is unpaved and very rough, all the time up and down at an average altitude of 4000 m”.

Ausangate circuit. An alternative to the valley ride to Pitumarca.

Salcantay. According to Ésteban Cortez, the Salcantay trek from Mollepata to Santa Teresa is better suited to cycling than the Ausangate route, in part because of its greater downhill tendency. From Santa Teresa you might well be able to ride to Machu Picchu.

Cordillera Blanca. We’re now looking seriously at northern Peru as a destination. The roads pass temptingly close to giant mountains.

GPS

IGN maps use the WGS84 datum and the UTM grid system, both of which are ideal for GPS. WGS84 is a model of the shape of the globe. UTM – Universal Transverse Mercator – is a convention for fitting rectangular grids to regions of its surface.

UTM divides the surface into a number of zones, each spanning 6 degrees of longitude and 8 of latitude (except that some Scandinavian countries have been granted waivers, and the system breaks down at the poles).

Within each zone the earth’s surface is roughly planar, and positions may be defined by rectangular coordinates, an easting and a northing. Note that northings are used in the southern hemisphere as well as the northern, so that (unlike latitude) the grid number increases as you go north.

The grid for any zone extends beyond it, but gives increasingly poor match to distances on the ground. The northings and eastings within a zone don’t start at 0 and end at (say) 100000; they start at one arbitrary-seeming number and end at another.

Eastings and northings are in units of metric distance. Hence UTM grid lines correspond to natural map scales. The northing in the northern hemisphere is your distance north of the equator. The easting is always given before the northing, and conventionally either they are given to the same number of digits, or the northing receives one digit more. The reason for the extra digit is that a northing kilometre is specified by 4 digits and an easting kilometre by 3.

However our Gamin GPS unit requires an extra zero in front of the northing so that easting and northing have the same number of digits.

IGN 1:100000 maps each cover half a degree of latitude by half a degree of longitude with no overlap. Hence any sheet lies entirely within a UTM zone. Unfortunately Cusco is very close to 72°W. To the west the zone is 18L; to the east it is 19L. GPS units know which zone to use. The zone numbers are given in the map legends.

The blue grid on IGN maps shows the grid numbers. Some leading digits which change slowly are printed as occasional superscript prefixes. I always give numbers in full.

Subsidiary grids are shown with ticks of various colours, and give references for other systems and zones. These may be ignored.

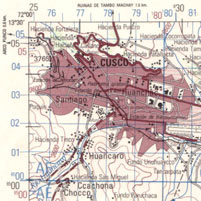

This map shows Cusco and the grid markings. A grid square – 1cm by 1cm on the page – is 1km by 1km on the ground.

Hacienda Zocorropata is at

| 19 L 0179200 UTM 8504900 |

GPS is a nice toy but not essential.

Some of this information is taken from Don Bartlett’s web site. [Dead link.]